OPERATION LEGACY

A UNIQUE DAY-BY-DAY REMEMBRANCE, 2014 - 2018

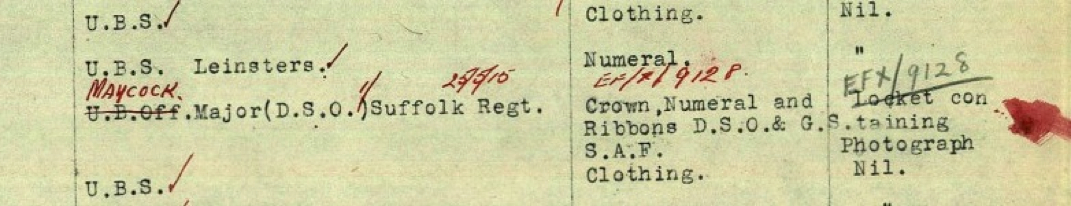

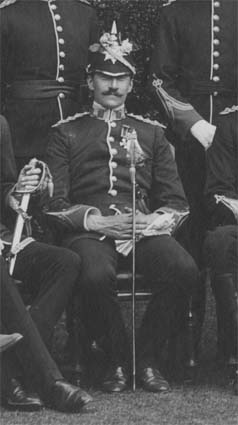

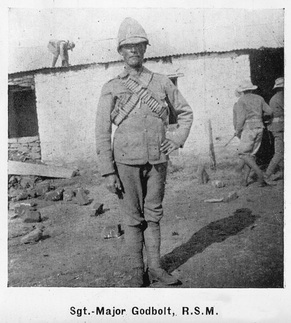

follow below, the great war service of the suffolk regiment,

from mobilisation to the armistice

from mobilisation to the armistice